The skin condition known as rosacea is a common and serious disorder that is underrecognized and undertreated. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, rosacea affects at least 14 million US adults, or 1 in every 10 individuals.1 According to the National Rosacea Society (NRS), that number is now estimated to be 16 million.2 Despite this relatively high incidence, the diagnosis of rosacea is often delayed or is never made.2 The consequence is needless suffering for many patients.

“Rosacea’s impact on appearance can be a disabling blow to the emotional and social lives of those who suffer from this poorly understood condition,” said Mark V. Dahl, MD, Chairman of the NRS Medical Advisory Board.3 “In addition, the stress of facing friends, family, and coworkers can act as a trigger for flare-ups, leading to a tailspin that can become increasingly hard to bear.”3

If brought to the attention of a dermatologist, however, rosacea can be effectively managed. Proper treatment results in marked improvement in skin, and therefore in the social and emotional impairments reported by patients with rosacea.

Rosacea is a medical condition with biological underpinnings; it is not a cosmetic problem. Its underlying features are inflammation and vascular reactivity, which lead to erythema and papulopustules. Although proper skin care management, along with topical and oral treatments, can improve many of the symptoms of rosacea, there are still unmet medical needs. Current treatments help with the papulopustules of rosacea, but they are not very effective in treating the redness that concerns so many patients. New agents currently in development have mechanisms of action that address this common characteristic.

The exact incidence of rosacea is unknown, because a uniform diagnosis is lacking and many patients with rosacea remain undiagnosed. The accepted incidence is 10% among fair-skinned individuals, the population that is most likely to be affected by rosacea, based on a large Swedish study.4 Although rosacea predominantly affects very light-skinned people, it can occur in individuals of any race or skin tone,5 and is believed to affect approximately 4% of those with darker skin.6,7 Up to 35% of Americans have affected family members; therefore, a genetic link has been proposed.8

Common Triggers

Many patients with rosacea report that environmental and other factors serve as triggers for flares. Although the list of potential rosacea triggers in each individual may be unique and lengthy, a survey of 1066 patients with rosacea documented common factors, including sun exposure (81%), emotional stress (79%), hot weather (75%), wind (57%), heavy exercise (56%), alcohol consumption (52%), hot baths (51%), cold weather (46%), spicy foods (45%), humidity (44%), indoor heat (41%), certain skin care products (41%), heated beverages (36%), and certain cosmetics (27%).9 Avoidance of obvious irritants, therefore, is helpful in the management of rosacea, but it is rarely sufficient.

A potential role for microbial organisms in the pathogenesis of rosacea has been a long-standing assumption. According to Del Rosso and colleagues, current evidence suggests that a microbial source is not mandatory for the development of rosacea; however, proliferation of Demodex folliculoru may incite a flare by triggering an immune response that is dysregulated and augmented in patients with rosacea.10 The most recent studies suggest that the important factor is not the mere presence of Demodex, because the organism is also found in skin that is not affected by rosacea, but the magnitude of the infestation.11-13

The Pathophysiology of Rosacea

The pathophysiology of rosacea has become an active area of research in the past decade, especially with the increasing understanding of the role of inflammation in many diseases. Rosacea is now understood to be an inflammatory disorder, based on the finding of an abnormal innate immune response system in persons with “rosacea-prone” skin.10

Del Rosso and colleagues recently elaborated on what they call the 2 inherent characteristics of rosacea-prone skin: neurovascular dysregulation and inflammation that produce physiochemical and structural changes in the skin.10 In their review of rosacea as an inflammatory disorder, Del Rosso and colleagues wrote, “Current evidence supports neurovascular dysregulation and altered immune response as integral components of vasodilatory reactivity and ‘neurogenic’ symptoms such as stinging and burning.”10 They noted that neurovascular dysregulation causes vasodilation and neurosensory symptoms, whereas an increased immunologic response to triggers activates an acute and chronic inflammatory response.10

With this hyperreactive immune system as background, environmental triggers can incite an exaggerated immune response. This triggering of the innate immune response system induces a signaling cascade of inflammatory factors that lead to chronic inflammation and an altered vascular state. Part of this inflammatory response most likely involves the toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), which is a pattern recognition receptor that is expressed in the skin of patients with rosacea, but not in other people; abnormal TLR2 function may explain enhanced inflammatory responses to environmental stimuli.14

In explaining the facial erythema (or redness) of rosacea, Del Rosso and colleagues pulled all these factors together to construct a picture of inflammation and vascular reactivity that includes an augmented innate immune response (ie, an increase in TLR2, cathelicidin precursors and peptides, and kallikrein-5); changes in the vasculature (ie, increased vascular endothelial growth factor, increased mast cells, and downstream effects of LL-37); neurovascular dysregulation (ie, vascular response, vasodilation, and neurosensory symptoms); dermal matrix degradation (ie, an increase in reactive oxygen species and matrix metalloproteinases, and a decrease in antioxidant reserve); vasodilation (ie, neurovascular dysfunction and increased nitric oxide leading to dilation and increased blood flow); and rosacea dermatitis (ie, stratum corneum barrier dysfunction and an increase in cytokines).10

Diagnosis

There is no available test for rosacea. The diagnosis requires an elevated index of suspicion based on the clinical manifestations.

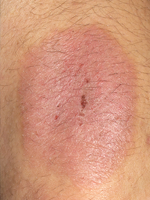

To establish the diagnosis of rosacea, at least 1 of the following primary features must be present: facial erythema for at least 3 months (ie, nontransient), transient erythema (ie, flushing and blushing), papules and pustules (ie, pimples), or telangiectasia (ie, small dilated blood vessels near the skin’s surface).15 Secondary features that may occur, but are not necessary for diagnosis, include burning or stinging, plaques, dry appearance, edema, ocular manifestations, peripheral location, and phymatous changes.15

The 4 Subtypes of Rosacea

Rosacea is classified into the following 4 subtypes—erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular, and each may require different treatments.15,16

1. Erythematotelangiectatic rosaceais considered the most common subtype. The common characteristics are flushing and persistent central facial erythema, with or without telangiectasia. Patients with this subtype experience prolonged (≥10 minutes) flushing, which can result from environmental triggers. Skin sensitivity is often described as burning and stinging after the application of topical agents. Patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea may also have telangiectasias that contribute to overall redness, a sign of this subtype and the least treatable with available medications. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea often resembles chronic sun damage, from which it should be differentiated (although the 2 can occur concomitantly). Other disorders to rule out are photosensitivity reactions and the butterfly rash of lupus.15,16

2. Papulopustular rosaceais characterized by persistent central facial erythema with transient, central facial papules or pustules, or both. This type is marked by bumps and pimples (and in severe cases, nodules) that are a result of chronic inflammation. Persistent erythema of the central face, subtle telangiectasias, facial edema, and ocular inflammation may also be present. Papulopustular rosacea must be differentiated from acne, which typically occurs in younger persons and may emerge on areas other than the face.15,16

3. Phymatous rosaceais a disfiguring form of rosacea that is uncommon in women and develops over years. It is marked by thickened skin, irregular surface nodularities and enlargement often involving the nose (the “W.C. Fields appearance”), but sometimes also the chin, cheeks, forehead, ears, and eyelids. Patients fear this manifestation of the disease, but few actually develop it, especially with proper treatment.15,16

4. Ocular rosaceais characterized by foreign-body sensation in the eye, burning, stinging, itchy eyes; ocular photosensitivity (light sensitivity); blurred vision, telangiectasia of the sclera or other parts of the eye, or periorbital edema. Ocular rosacea may be misdiagnosed unless it is accompanied by other features of rosacea, but in 20% of patients with rosacea, ocular signs are the first indication of the disorder. An ophthalmic consultation is warranted to avoid further complications of this manifestation of rosacea.15,16

A 2013 NRS survey of patients with rosacea focused on the signs and symptoms of this condition.17 Of the 1072 patients surveyed, 31% said that flushing was their first symptom and 24% said that persistent redness was their first sign of rosacea. In addition, although the progression of rosacea signs and symptoms varied considerably among patients, 94% said that flushing was the first or second sign and 57% said it was persistent redness.17

“Rosacea goes undiagnosed in so many people because the most common initial symptoms—and persistent redness—are often overlooked or mistaken for something else, such as sunburn,” commented John E. Wolf, Jr., MD, Chairman, Dermatology Department, Baylor College, Houston, TX.

The Psychosocial Toll of Rosacea

According to a 2012 NRS survey of 801 patients with rosacea, those with any rosacea subtype can experience the negative social impact of this condition.18 In the survey, 61% of patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (characterized by redness) said that their rosacea had inhibited their social lives; that percentage rose to 72% in patients with moderate or severe redness; 77% in patients with papulopustular rosacea; and 85% among patients whose symptoms included phymatous rosacea. Among the respondents who had the eye irritation of ocular rosacea, 71% said that their social lives were inhibited.18

Conclusion

Rosacea is a serious medical condition that is often underdiagnosed and undertreated but can cause considerable distress, impact daily function, and disrupt social relationships—in other words, rosacea can clearly diminish a patient’s quality of life. Current treatments are effective, but only to a point. This medical disorder will benefit from new therapies that can impact the underlying biology of rosacea and provide improved control of the mechanism of rosacea and improved quality of life for patients.

References

- American Academy of Dermatology. Rosacea: who gets and causes. www.aad.org/skin-conditions/dermatology-a-to-z/rosacea/who-gets-causes. Accessed April 15, 2013.

- National Rosacea Society. Red alert: rosacea harbors social minefield for more than 16 million Americans. www.rosacea.org/press/20130401.php. April 1, 2013. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- National Rosacea Society. Rosacea awareness spotlights social impact, warning signs. Rosacea Rev. Spring 2013. www.rosacea.org/rr/2013/spring/article_1.php. Accessed May 23, 2013.

- Berg M, Lidén S. An epidemiological study of rosacea. Acta Derm Venereol. 1989;69:419-423.

- Abram K, Silm H, Oona M. Prevalence of rosacea in an Estonian working population using a standard classification. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:269-273.

- .McAleer MA, Fitzpatrick P, Powell FC. Papulopustular rosacea: prevalence and relationship to photodamage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:33-39.

- Woolery-Lloyd H, Good E. Acne and rosacea in skin of color. Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;24:159-162.

- National Rosacea Society. Widespread facial disorder may be linked to genetics. Press release. June 2, 2008. www.rosacea.org/press/archive/20080602.php. Accessed April 15, 2013.

- National Rosacea Society. Rosacea triggers survey. www.rosacea.org/patients/materials/triggersgraph.php. Accessed April 15, 2013.

- Del Rosso JQ, Gallo RL, Kircik L, et al. Why is rosacea considered to be an inflammatory disorder? The primary role, clinical relevance, and therapeutic correlations of abnormal innate immune response in rosacea-prone skin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:694-700.

- Sattler EC, Maier T, Hoffmann VS, et al. Noninvasive in vivo detection and quantification of Demodex mites by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1042-1047.

- Zhao YE, Wu LP, Peng Y, Chang H. Retrospective analysis of the association between Demodex infestation and rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:896-902.

- Forton FM.Papulopustular rosacea, skin immunity and Demodex: pityriasis folliculorum as a missing link.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:19-28.

- Yamasaki K, Kanada K, Macleod DT, et al. TLR2 expression is increased in rosacea and stimulates enhanced serine protease production by keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:688-697.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: Report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Baldwin HE. Diagnosis and treatment of rosacea: state of the art. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:725-730.

- National Rosacea Society. New patient survey defines progression of rosacea. July 8, 2013. www.rosacea.org/weblog/new-patient-survey-defines-progression-rosacea. Accessed July 18, 2013.

- National Rosacea Society. Rosacea patients feel effects of their condition in social settings. Rosacea Rev. Fall 2012. www.rosacea.org/rr/2012/fall/article_3.php. Accessed April 12, 2013.